Rigorous training for the nation’s top spelling bees can prepare kids for lifelong achievement

by Leigh Jones

Courtesy WORLD Magazine

The word is: quokka,” the announcer said in a made-for-radio baritone.

\\\”Quokka?” Fourteen-year-old Raksheet Kota’s voice held the slightest inflection of inquiry, as though he had never heard the word before. “May I have the definition?”

Raksheet, one of three finalists in the Houston Public Media Spelling Bee, had already spelled his way through six rounds in the nation’s biggest—and most competitive—regional competition. Only the top two would advance to the Scripps National Spelling Bee in Washington, D.C. It was Raksheet’s last chance, after competing in the Houston bee for five years. In 2014, he took 10th place, rising to fourth and then third in subsequent years. He’d spent nearly half his life preparing for this moment.

“Quokka: A small wallaby inhabiting islands and swampy areas in southwestern Australia,” the announcer intoned.

The corners of Raksheet’s thin lips rose slightly, a rare show of emotion for the eighth-grader. But it still wasn’t clear whether he knew the word. If not, it wouldn’t be for lack of practice. Raksheet entered his first spelling bee competition in first grade, in a league open only to Indian-American students. The North South Foundation (NSF) has been compared to America’s minor league system for baseball —with one big exception. While minor league ballplayers may never make it to the big leagues, NSF kids have come to dominate national spelling and other academic contests, raising the level of competition and speculation about what makes them so successful.

“May I have the language of origin?” Raksheet asked, continuing a routine ingrained after years of repetition. Even if they think they know how to spell a word, NSF-trained competitors follow the same pattern of questioning before uttering the first letter of their answer.

NSF began holding spelling bees in 1993 with one goal: improve English proficiency among Indian-American students so they could raise college entrance exam scores and get into the universities of their choice. In 1994, the all-volunteer organization added a vocabulary bee. Nine years later, NSF celebrated its first champion in the prestigious Scripps competition. But Indian-American spellers didn’t solidify their dominance until 2008, the next time an NSF student won the national contest. Since then, they’ve held an unbroken, nine-year streak.

Their success has forced Scripps organizers to make substantial changes to increase the competition’s difficulty. In 2013 they added a computerized spelling test before the semifinal rounds to help narrow the list of finalists. In 2016, they abandoned the list of 25 championship words in favor of 25 championship rounds that could include as many as 75 words between the three finalists. But the 2016 contest still ended in a tie, for the third year in a row. 2017 finalists took a written test with 12 spelling words and 12 vocabulary words before the final rounds begin. In the event of a tie, judges open the sealed results of the written test in hopes of declaring just one champion.

Valerie Miller, a Scripps spokeswoman, wouldn’t address the success of Indian-American students specifically but admitted organizations and competitions like NSF and the South Asian Spelling Bee help prepare spellers to do well at the national level. Standing onstage under the glare of lights for an event broadcast on national television can be daunting. Spellers like Raksheet have learned how to overcome performance jitters through years of practice.

“Quokka. Can I have the word in a sentence, please?” Raksheet continued to quiz the announcer in Houston, repeating the word before every question.

It’s a routine his father and mother, Satya and Rupa, have listened to thousands of times. Raksheet studies words year-round, although his participation in math and science competitions has forced him to cut back on spelling drills in recent years. The family started with the Consolidated Word List, a compilation of 23,000 words used in spelling bees since the 1950s.

Once Raksheet had a “bank” of 10,000 words he knew how to spell, they started working with him on language patterns and derivations, which help competitors figure out how a word is spelled even if they’ve never seen it before. When he understood those patterns, they focused on exceptions. To stave off boredom, Satya quizzed his son while he watched televised soccer matches. At the height of his training, Raksheet went through the entire Consolidated Word List twice a year.

“Quokka,” Raksheet repeated for the last time, taking a deep breath before finally giving his answer—one word per heartbeat. “Q-U-O-K-K-A.”

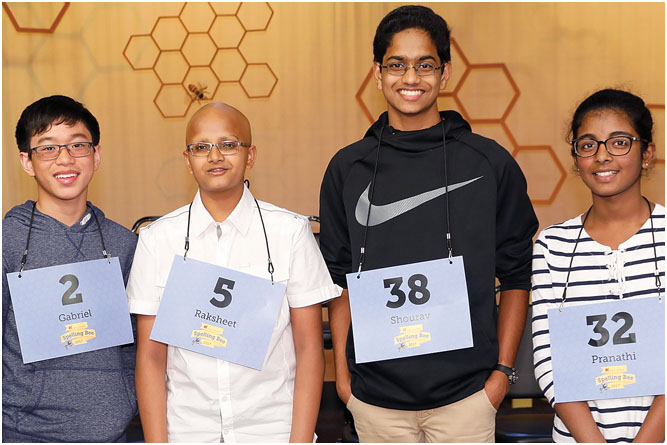

The correctly spelled Australian marsupial earned Raksheet his long-awaited trip to the national competition. Fellow eighth-grader and veteran NSF speller Shourav Dasari beat Raksheet to take first place in the 2017 Houston contest, but when they get to Scripps, they’ll be back on equal footing. Both boys beamed as they posed together for photos with their chest-high trophies.

Raksheet’s father and mother, computer programmers who emigrated from Hyderabad, insist Indian-American students aren’t predisposed to do well in spelling contests. They credit the community’s passion for education and emphasis on family involvement for fostering excellence. Indian-American families who participate in academic competitions pour as much into that effort as other families commit to baseball or soccer. But the dividends pay lifelong returns. For fun, Raksheet took a practice version of the SAT math test last year. He got a perfect score.

Leigh Jones lives in Houston with her husband and daughter. She is the news editor for The World and Everything in It and reports on education for WORLD Digital.