By the time Mahatma Gandhi returned to India from South Africa and became active in the independence struggle, there was already a wave of music nationalism being championed by the likes of Vishnu Paluskar, V.N. Bhatkhande and Subramania Bharati; traditional musical practices were being relocated from palace courts to the public arena. Soon after his arrival in India, realising its potential to bring people together, Gandhi adopted music as one of the instruments to mobilise the masses for the cause of swaraj.

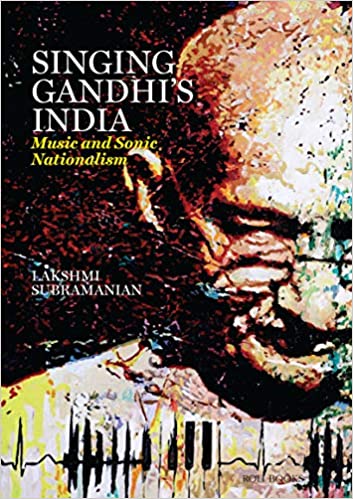

By the time Mahatma Gandhi returned to India from South Africa and became active in the independence struggle, there was already a wave of music nationalism being championed by the likes of Vishnu Paluskar, V.N. Bhatkhande and Subramania Bharati; traditional musical practices were being relocated from palace courts to the public arena. Soon after his arrival in India, realising its potential to bring people together, Gandhi adopted music as one of the instruments to mobilise the masses for the cause of swaraj.In Singing Gandhi’s India, historian Lakshmi Subramanian examines Gandhi’s relationship with music through his letters, significant events and other documents.

Leaning on bhajans

Subramanian begins by introducing the reader to the early nationalisation project aimed at collating and creating a new ‘classical’ tradition of Indian music: Hindustani classical in the north and Carnatic in the south. This reform project, however, led to the exclusion of the communities of the traditional practitioners such as the Devadasis in the south and the Ustads and Tawaifs in the north. Interestingly, according to Subramanian, Gandhi did not engage with this reform project; he felt the classical form of music demanded an intimate knowledge of technique. For Gandhi, music — whether it was a bhajan like Vaishnava Janato or a patriotic song like Vande Mataram — was a means of development of the “moral self” which was essential to become a satyagrahi. Subramanian writes that Gandhi saw the morning prayers as a way to inspire personal discipline and community singing as a means of mobilising people.

The book traces Gandhi’s relationship with music from the early days of the Sabarmati Ashram till the time of Independence. But Subramanian does not follow a chronological approach which can be confusing for a reader trying to understand the evolution of this complicated relationship.

However, the historian engages the reader by revealing the difficulties in interpreting the vast and frequently contradicting writings of Gandhi. In one instance, she writes about resisting the “temptation to speculate on the gendered dimensions” of Gandhi’s forthright instructions to women followers via his correspondence with Saraladebi Chaudhurani.

Moral lessons

She also examines Gandhi’s reflections — amounting to dismissing the requirement of public performance of religious songs to assert devotion to a religion — on the communal conflicts created by the singing of devotional songs at prayer times in front of mosques in the 1920s and his subsequent endorsement of the public performance of prabhat pheris (morning musical processions)in the 1930s as a political act.

It is fascinating to read how Gandhi remained committed to his idea of music as an important device to build a moral society despite several hurdles such as the opposition to the invocation of Lord Rama in the Ramdhun (Gandhi responded by saying Ram is universal and belongs to all religions) and the Hindu undertones of Vande Mataram.

Despite its uneven structure, the timing of the book helps the reader to delve deep into Gandhi’s use of music as a means of spiritual development and his failure in inspiring the masses to adopt a morally upright lifestyle. It also provokes the reader on contemplating how Gandhi who “admitted it was not possible to have politics without religion” would have reacted to the increasingly intertwined discourse of religion and nation in the country.

Singing Gandhi’s India: Music and Sonic Nationalism by Lakshmi Subramanian, is published by Roli Books, ₹495.

The author of this review, Basav Biradar, is an independent researcher and filmmaker; this review was originally published in The Hindu newspaper and is included here by the author’s permission.