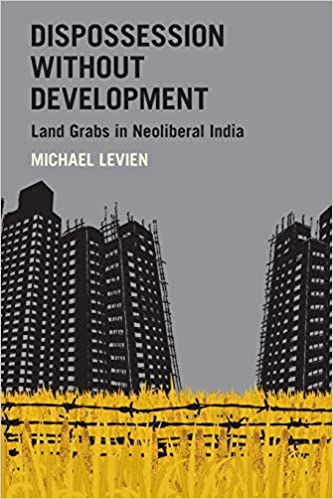

Dispossession without Development: Land Grabs in Neoliberal India. Michael Levien. Oxford University Press. Reviewed by Dr. Nikhil Deb in the LSE Review of Books blog; used here by permission.

In Dispossession without Development: Land Grabs in Neoliberal India, Michael Levien examines how the shift from state-directed capitalism to neoliberalism in India from the 1990s has led to a new regime of dispossession, in which land becomes ‘for the market’ rather than ‘for production’ and rural residents lose their land and livelihoods. Using the case study of Rajpura to evidence the consequences of Rajasthan’s transition to a ‘land broker state’, this rich, theoretically engaged book is sure to remain at the centre of academic discussions of development, dispossession, resistance and neoliberalism, writes Nikhil Deb.

Michael Levien expertly demonstrates how the ‘shift from state-directed capitalism to neoliberalism in the early 1990s led to the genesis of a new regime of dispossession’ (32) in India. This regime, as Levien argues, can be characterised as one of ‘land for the market’ instead of ‘for production’ as the Indian government dispossesses people and uses or sells the land for non-labour-intensive purposes. Such a shift brings about the question of whether dispossession of land by the government is predatory or beneficial for the nation’s development as the discrepancy between the farmer’s compensation and the market appreciation of the land is astounding. Levien’s theoretical engagement with classic to contemporary scholars and his employment of ethnographic insight exhibit a powerful example of the ways in which the global and the local can be integrated into a sociological analysis.

Of the two types of dispossession in postcolonial India, developmental and neoliberal, Levien argues that the driving causes of land dispossession changed dramatically during the latter regime. During the developmental period, India dispossessed people of their land for public projects. However, as the economy started to become more liberalised, creating a new level of demand for privately owned rural land from the 1990s onwards, the pressure of competition within the state and the temptation of legal and illegal rents provided the government with incentives to start dispossessing land for any reason that could be thought of. The neoliberal regime of dispossession reached its peak in the mid-2000s with Special Economic Zones (SEZs), which were effectively governed by private corporations, and became integral to the neoliberal Indian state (47-48).

Government dispossession of land in India increased after the end of colonialism, despite a cry for more significant social reform in Congress (33). This government seizing of public land is legally permissible under the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, which was passed during British rule to take private lands by force for public purposes (34). After its independence in 1947, India set on the path for development. Eventually, it undertook the Nehruvian model, which deepened the colonial legacy by perpetuating the exploitation of land and adding profit to private organisations without resettling the dispossessed or underprivileged.

Development dams — ‘the paradigmatic form of state-led development and potent symbols of national progress’ (35) — were the largest source of dispossession in postcolonial India. People were asked, as India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru told the oustees of one dam, to ‘sacrifice for the nation’ (42). However, as bad as this was, at least more of the land was for public use rather than private (43). In the early 1990s, with the neoliberal reckoning, demand for private land grew exponentially. Post-liberalisation growth was fuelled by Information Technology (IT) and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO), along with Major Multinational Corporations (MNC) like American Express, British Airways and General Electric.

Government dispossession of land in India increased after the end of colonialism, despite a cry for more significant social reform in Congress (33). This government seizing of public land is legally permissible under the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, which was passed during British rule to take private lands by force for public purposes (34). After its independence in 1947, India set on the path for development. Eventually, it undertook the Nehruvian model, which deepened the colonial legacy by perpetuating the exploitation of land and adding profit to private organisations without resettling the dispossessed or underprivileged.

Buy Dispossession without Development on Bookshop.