Vasco da Gama (1469‒1524) from Lisbon arrived in Kôzhikôde (Calicut, 11o25’ N, 75o77’ E) in 1498, during the reign of Nédiyirûppû Swarõpam Mãnava Vikraman Sãmõŧírí1. Consequently, the early years of the 17th century were busy for Europeans. Britain launched the English East-India Company (EEIC) in 1600 AD to explore India, seeking pepper and cardamom. The Netherlands established the Verenigde Nederlandsche Geoctroyeerde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) on a similar purpose in 1602. Staggering profits made by the EEIC and VOC in the following years enticed Christian IV (1577‒1648), king of Denmark–Norway Kingdom (DNK) to institute the Danish East-India Company (Ostindisk Kompagni, OK) in 1616 that operated, albeit with some spells of discontinuity, until the mid-19th century. Admiral Ove Gjedde (also, Giedde, Portrait 1) representing DNK king arrived in Ŧaraṅgampãdi, a sleepy coastal village in India (11°1’ N, 79°51’ E) in 1620 (ref. 2). None of these European trade missions then knew that their arrival was going to ignite a massive fire of geopolitical changes in the subcontinent in the following years.

Ŧaraṅgampãdi (Tranquebar, Trankebar), presently in Nãgapattinam (Nãgapattam) District, lies on the Coromandel Coast, c. 25 km south of Kãvéri-p-pûm-pattinam (Pûmpûhãr, pûhãr = estuary), a famous port during the times of the Çôlã s (3rd–13th centuries AD with vast interregna)4‒7 and c. 30 km north of Nãgapattinam town (10o77’ N, 79o83’ E). A 14th-century stone inscription retrieved in Ŧaraṅgampãdi identifies this town by a Sanskritic‒Tamil name Śaḍãṅganpãdi (Śaḍ-aṅgan — six-armed, Sanskrit; pãdi — a residential locality, Tamil). A popular, but less-convincing, explanation of Ŧaraṅgampãdi is ‘singing waves’: ŧaraṅgã (Sanskrit, Sinhalã) — waves, pãdi (Tamil) — that sing. Interpretation of pãdi to mean singing is incorrect, because pãdi evolves from padai-vēdû meaning an ‘army camp’. No notable reference to Ŧaraṅgampãdi exists in either ancient or medieval Tamil literary works, although many of Sangam period (200 BC‒200 AD) speak of Pôrayãr 5, 6 (11o02’ N, 79o83’ E), a little south of Ŧaraṅgampãdi.

Author P. S. Ramanujam (PSR) is an emeritus professor of photonics at the Danmarks Tekniske Universitet, Lyngby. Further to making valuable contributions to photonics, he has variously written on Ŧaraṅgampãdi and the science promoted by Scandinavians there. Videnskab, oplysning og historie i Dansk Ostindien (2020, Syddansk Universitetsforlag) referring to Danes in Ŧaraṅgampãdi is his yet another volume, co-written with Lise Groesmeyer and Niklas Jensen.

To Unheard Voices: A Tranquebarian Stroll (hereafter, Unheard Voices). High-quality printing and pleasingly laid-out pages are fascinating. Superb photographs of the present-day Ŧaraṅgampãdi made by PSR and elegantly restored illustrations extracted from past documents of Ŧaraṅgampãdi enhance the book’s quality. Fourteen elegantly captioned chapters (p. 21‒354) form this book: from the arrival of Roelant Crappé — a Dutch sailor and a director of OK — in Kãraikkãl (10o92’ N, 79o83’ E), 15 km south of Ŧaraṅgampãdi after his cutter Øresund was annihilated by the Portuguese commander Andre Botelho da Costa in 1619 to the end of Danish interests in India in 1845. This book describes Ŧaraṅgampãdi’s chequered history lucidly. PSR literally walks us — readers — through the streets of Ŧaraṅgampãdi and neighbourhood, maintaining tempo until end. PSR narrates historical details and incidences and places simply and gracefully, supplementing with stories of people associated with the OK — either directly or indirectly. While talking of Henning Munch Engelhart, a pastor in the Zion Church (ZC) in Ŧaraṅgampãdi, PSR alludes to Engelhart’s thesis entitled det Tanker om Oplysnings Udbredelse blandt Indianerne (1790), which captures Engelhart’s thoughts on the sociology of Indians8. Engelhart urged that Indians need to be equipped with knowledge to achieve clarity, eschewing despotism and superstition. Engelhart’s use of oplysning (Danish) meaning ‘clarity’, ‘enlightenment’ is brilliant. Engelhart argued that the saving measure was to create a new construct that will ensure equality between Indians and the Europeans living in India: Indians were to become fully aware of human rights, and thus, aware of their own rights. The seeds for such a bold thinking in Engelhart were probably sown by the Magna Carta Libertatum (1215 AD). Engelhart argued in favour of five knowledge tenets and their impartment to Indians was critically necessary. Two of them — as relevant to readers of this journal — were enabling Indians with a factual narrative of Indian history and skills in western science, especially, astronomy, mathematics, and natural history. Although a faint thread promoting Protestantism runs throughout Tanker om Oplysnings Udbredelse, the silver lining is that this thesis powerfully contends equipping Indians with knowledge, and thus empowering them to seek ‘truth’. Such a thinking was conspicuously absent among the British in India, even in later decades. The English-Education Act‒1835 marshalled by Thomas Babington Macaulay and William Bentinck is one example of an illusory do-good activity in British India, discretely aiming at ‘developing’ Indians to garner a body of clerks to serve the British and not at total empowerment.

Ove Gjedde arrived in Ŧaraṅgampãdi in 1620, after vain bids to build a fort in Kandy (7o17’ N, 80o39’ E). Following a treaty signed with Raġûnãŧã Nãyakã (r. 1600‒1634) in Nãgapattinam in November 1620, Gjedde could build Fort Dansborg (FD, Festningen Dannisborg) in Ŧaraṅgampãdi9 in a 6 x 3 mi2 (c. 10 x 5 km2) area (see an impressive 2-page map of Ŧaraṅgampãdi, 1733, by Gregers Daa Trellund of the Danish Military Engineers, in p. 24‒25). With the building of FD, seeds for a Danish settlement in Ŧaraṅgampãdi were sown, later spreading to the Nicobar Islands and parts of Calcutta. Donald Ferguson, a British chronicler of the late 19th century says10, p. 625:

‘The captain, Rodant Crape (Roelant Crappé), to effect a landing, is said to have wrecked his ship off Tranquebar, at the expense, however, of his crew, who were all murdered. He then … obtained Tranquebar for the Danish Company, with land around five miles long and three miles broad. A fort was built, and in 1624 Tranquebar became the property of the King of Denmark, to whom the Company owed money.’

In p. 39‒53, brief details from the diary maintained by Jón Ólafsson, who came Ŧaraṅgampãdi from Iceland, written in 1624‒1625, are available. Ólafsson’s diary11 is an interesting document, because it covers details of life and culture in Ŧaraṅgampãdi, although we know that much of it is either exaggerated or distorted due to poor understanding. What is noteworthy, nevertheless, is that an Icelander from a landscape that generally experiences sub-zero temperatures, dared to come to a humid, tropical land in the 17th century, lived for two years, and minuted what he saw and experienced!

An elegant map of the 1800s-Ŧaraṅgampãdi by Peter Anker (1744‒1832), DNK Governor-General (1786‒1808) is available in p. 69. Anker was not only a popular administrator, but a skilful artist as well, who made beautiful drawings of various Indian objets d’art and portraits, presently displayed in Oslo-University museum. An impressive portrait of one Suppremania Setti (read as Sûbramania Çétty) by Anker is available in p. 244. Suppremania was employed by Thomas Christian Walter — a Danish privy councillor — as his interpreter (ḍûḃãś, ḍvi-ḃãśi). Suppremania’s portrait reminded me of Ãnanda Ranga (1709‒1761), Joseph-François Dupleix’s ḍûḃãś in Põndiçéry. Reproductions of Anker’s artworks of Kûmbakônam and Ŧanjavûr temples and Mahãbalipûram relics can be seen at https://www.khm.uio.no/forskning/samlin-gene/etnografisk/artikler/peter-ankers-kunstsamlinger-og-sor-india.html.

Western astronomy was enthusiastically pursued in southern India as early as the 17th century. Bordeaux-born Jesuit Jean Richaud (1633‒1690) observed the comet ‘C/1698 X1’ in Põndiçéry (11o55’ N, 79o49’ E) in December 168912. A Venus transit occurred on 3 June 1769, attracting the attention of several stargazers throughout the world: for example, James Cook witnessed this event in the Endeavour anchored in Tahiti (17°40’ S, 149°25’ W)13. In the chapter A forgotten astronomer — a forgotten blessed soul (p. 127‒150), PSR speaks of Henning Munch Engelhart’s astronomical observations. Before arriving in Ŧaraṅgampãdi, Engelhart had trained in astronomy with the Royal Astronomer Thomas Bugge (1740‒1815) in Copenhagen. He established an observatory in ZC’s tower (ZCO), the highest point in the coastal Ŧaraṅgampãdi14. A transit instrument (TI) mounted in east‒westerly axis, enabled to rotate in north‒southerly axis, and a wall-mounted astronomical clock existed in ZCOp. 132‒134. That the TI used by Englehart must have been similar to the one presently displayed in Kroppedal Museum, Taastrup (Fig. 7.3, p. 136) remarks PSR. Details of the ZCO, extracted from the Tranquebarske Dokumenter (1786‒1790) and reproduced in p. 134‒137, will benefit anyone interested in the 18th-century astronomy in India. Engelhart determined the latitude and longitude of Ŧaraṅgampãdi, although the credit for this determination was erroneously attributed to Michael Topping (1747‒1796, Madras Astronomer) by his successor John Goldingham (1767‒1849)15. After comparing results with predicted times of eclipses of Jupiter’s satellites in Greenwich (51o48’ N, 0o0’ E), Engelhart determined ‘time’ in Ŧaraṅgampãdi as being in advance of Greenwich by 5 h 18 min 58 sec, impressively close to the present determination. Engelhart was a key force in founding det Tranquebarske Selskab (the Tranquebarian Society, TS), which aimed atp. 131:

‘…improving scientific methods and information for the betterment of Denmark and the local society in India and further improving European knowledge about India’.

The TS was the third oldest of learned European societies east of the Cape of Good Hope: the other two were the Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen established by Jacob Cornelis Matthieu Radermacher in Jakarta in 1778 and the Asiatic(k) Society by William Jones in Calcutta in 1784 (ref. 16).

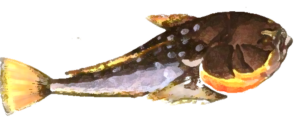

Christoph Samuel John (1747‒1813), a German by birth and ordained as a priest in Copenhagen, spent nearly four decades in Ŧaraṅgampãdi. In 1789, John reasoned for a botanical garden with Ŧaraṅgampãdi’s administrators for raising plants from all over India and creating a space for the entertainment and education of locals16. He established a garden that housed medicinal plants from all over peninsular India and Dutch Ceylon (Sri Lanka). John was in touch with William Roxburgh in Madras by regularly sending plants for determination and description17. John believed in and advocated ‘Natural Theology’ (Theologia naturalis, sive liber creaturarum, … 1488 AD, https://archive.org/details/ita-bnc-in2-00001588-001/page/n9/mode/2up, accessed 6 February 2022) promulgated by the Catalan scholar Ramon Sibiuda (1385‒1436) and reinforced by English Naturalist John (W)Ray (1627‒1705) as a means of evangelizing. John considered Nature close to his heart and argued that the Divine could be experienced through scientific exploration; in support of this theological‒natural-historical perspective, he wrote Nature, in contrast to popular books on experiencing divinity through scriptures. With this philosophical underpinning, John sent plant and animal materials to experts within India and overseas. For example, he sent samples of Diploknema butyracea (previously Bassia butyracea, Sapotaceae) to William Roxburgh in Madras for determination and description. John’s interest in sending D. butyracea to Roxburgh was because this chicle-yielding tree was used by Indians variously: to treat tonsilitis, rheumatism, itches, ulcers, and to manage haemorrhages. This tree was also used to obtain çiûrí (something similar to milk-butter), fodder for cattle, and wood amenable to carpentry — an amazing multi-use plant! John was passionate to know more of animals than of plants in and around Ŧaraṅgampãdi. He documented his notes on animals in a professional manner. One example is his description of the long-nosed stargazer Uranoscopus lebeckii (Fig. 1) (currently Ichthyscopus lebeck; Pisces: Uranoscopidae) in the article entitled ‘Beschreibung und Abbildung des Uranscopus lebeckii’ in der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin (1801, 3, 283‒287). He sent several fish specimens to Marcus Eliezer Bloch, an eminent ichthyologist in Berlin, who included details of the materials sent by John in his multi-volume Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische (1782‒1795). John also shipped preserved snakes from India to Johann Reinhold Forster, a Halle zoölogist‒herpetologist, supplementing those dispatches with notes on snake poisons and locally used antidotes. Relevant would it be to recall here the painstaking efforts of Çéngalpattû Sûndaramûrŧy Môhanavélû (formerly of the Presidency College, Chennai) to compile and annotate original documents archived both in several Indian and European libraries referring to the science promoted by several of the DNK (a.k.a. Halle) missionaries, including Christoph John.

Copiously complemented with photographs of tombstones and obelisks in the Ãŧaṅkarai-Street (previously Nygade ‒ New Street) cemetery in Ŧaraṅgampãdi, the chapter the old cemetery (p. 257–271) recalls the lives and works of DNK medical doctors such as Friedrich Wilhelm Rühde, Theodor Ludvig Frederich Folly, and Samuel Benjamin Cnoll between 1620 and 1767. Cnoll is remembered for the Laboratorium Chymicum (= pharmacy) established in 1732 (ref. 19). The text referring to the general health of Indians in Ŧaraṅgampãdi by Rühde (vide Classenske Litteratureselkskab, 1831) fascinates. As an example, I will quote PSR’s words paraphrased from Rühde p. 266 on German measles and malaria:

‘In temperatures ranging between 37 and 60oC, people tended to develop Rubella–German measles. After a few years, the skin [of the European settlers] became less sensitive and people suffered less. During periods of flooding, malaria became prevalent. Intermediate fevers were cured with quinine — however this did not seem to work with Indians. In the case of two Europeans treatment with quinine was not enough: Rühde cured them with strychnine.’

The above text attracted my attention for diverse reasons. Given that foundations of immunology laid by Emil Adolf von Behring (1854‒1913) through serum therapy and by Paul Ehrlich referring to ‘specialized cells of the immune system’ happened only in the later decades of the 19th century, Rühde’s use of ‘less sensitive’ struck me as prophetic, because much science has progressed in later years, foreshadowing tissue sensitivity, susceptibility, resistance, and of course, the discipline of immunology. Rühde’s comment linking flooding with the greater incidence of malaria is interesting, since we know today that the mosquito, the intermediate between humans and the pathogenic protozoan, necessarily requires water during its early development stages. Remainder of the chapter refers to Rühde’s observations on various aspects of medicine: methods used by local doctors (vaidyan-s), children’s common diseases, public healthcare, daily consultations, and inflammation of the intestines. PSR renders Rühde’s notes on leprosy p. 270:

‘Leprosy is a bigger problem in the colony. It was brought to the Coromandel Coast by Africans kept as slaves by the Dutch in Nagapattam (Nãgapattinam)’.

grabbed my attention, since leprosy (Hansen’s disease, causal agent: Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacteriaceae) was known in India for ages as kûśtã, recorded in ancient scriptures and medical treatises of later times20. That the African-bonded labour brought to India by the Portuguese introduced leprosy in India does not sound right. Moreover, few published articles speak of Africans in Pazhavérkãdû (Pûlicãt, 13°42’ N; 80°32’ E), a popular port of the Coromandel Coast when the Portuguese arrived there in the 15th century21, 22. Thought-provoking comments on diabetes mellitus (DM) occur in p. 270.

‘That DM affects a lot of Indians. It is incurable because the locals refuse to give up vegetable diet. During later stages of the disease, people get carbuncles in the face and/or neck, when DM is lethal.’

In the 1700s, physicians knew that food habits and dietary changes would help diabetes management. However, curiously, they advised patients to eat fatty food and meat and consume large quantities of sugar(!?). Therefore, Rühde’s comment that locals refusing to give up vegetable diet does not surprise. Only in the early 1870s, Apollinaire Bouchardat23 clarified ‘food rationing’ was an ideal measure in DM management and this explanation changed the future of DM management.

Chapter 10 Philology comes to town (p. 217‒232) consolidates the emergence of Ŧaraṅgampãdi as a dynamic hub of learning: for example, Christoph John was exploring local flora, fauna, and literature. Theodor Folly was documenting the medical skills of the vaidyan-s. Rasmus Christian Rask’s (1787‒1832) arrival in Ŧaraṅgampãdi in 1823 complemented the Danish explorations of traditional-Indian knowledge, wisdom, and biological wealth. Rask was a self-trained philologist, who looked for the root language. His inferences were via comparison and contrasting of languages. He considered etymology as a natural science and regarded encyclopaedic and grammatical connections in a language as critical links. For example, he studied the Zend — Zoroastrian language — and articulated the rules for its inflexion and grammar. He came to India to acquire and read palm-leaf manuscripts. While staying in Madras (Vépéry Mission, Tranquebar Mission) along with Johann Rottler, Rask investigated the linguistic finesse of Tamil (Fig. 10.4, p. 225). The following textp. 224 is one from several of Rask’s comments on Tamil langauge,

‘Tamulisk ‒ (Tamla or Tamulah) called High Tamil, is estimated to be the oldest and most indigenous language and is a source for other languages. It is also distinguished by a richer and more self-contained literature.’

Chapter 10 is full of such amazing details (e.g., extracts from Rask’s diary for August 1821) that are not only fascinating, but they also offer exciting insights into the life and culture of the Tamils in the 1800s.

DNK (Halle) missionaries Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg (1682‒1719), Heinrich Plütschau (1676‒1752), Gerhard König (1728‒1785), and Johann Rottler (1749–1836) have been elaborately talked about by PSR. I have chosen to refrain from speaking about these men, because we know considerably about them. Nonetheless, I will refer to the less-known Daniel Pulley, Thomas Christian Walter, and Gowan Harrop briefly. PSR identifies these men as key players in the Danish Ŧaraṅgampãdi. Daniel Pulley, a half-Tamil dwi-bãśi, a grandson of one Johann d’Almeida, lived in Ŧaraṅgampãdi in the second half of the 18th century. Born in 1740(?), he was talented in German language, which earned him the position of being an assistant to Christoph John. From 1755, he taught Tamil to missionaries arriving in Ŧaraṅgampãdi. From 1782, when Peter Hermann Abbestée (1728‒1794) was the governor, Daniel was promoted as a ‘first-level’ dwi-bãśi. In this role, he established a cordiality between the Danes and Ŧûlajã Bhôslé, the rãjã of Ŧanjãvûr. Because of Daniel’s Ûrdû fluency, he, representing the Danes, mediated with Lãlã Sahéb, commander of Hydér Alī’s army, and prevented an attack of Ŧaraṅgampãdi by Hyder’s army camping in Porto Novo near Çidambaram. In 1780 and 1781, Daniel served as a Danish emissary to Hydér in Mysore. The role played by Daniel in the political and religious life of Ŧaraṅgampãdi cannot be gainsaid. His letters written in Tamil in 1782‒1785, archived at the Rigsarkivet, vouch for his influencing role. A photo reproduction of one letter written in Tamil by Daniel is available in p. 157. Daniel’s other letters, rendered in English in p. 158‒185, offer clarity on troop movements and the problems faced by ordinary people during Anglo‒Mysore wars. Daniel’s letters supplied in Unheard Voices will undoubtedly be relevant to many an investigator.

Botched by his unsuccessful jaunts in classical western music in Copenhagen, Thomas Christian Walter sailed to India and became a civil servant in Ŧaraṅgampãdi. He rose in ranks quickly as the chief financial officer, second to the governor. Details of his probate — an informative document referring to the lives and works of a few of his more-important colleagues — are available in chapter 13, A musician and his tragic fate (p. 273‒278).

Gowan Harrop of non-Danish lineage arrived in Ŧaraṅgampãdi in 1774 and joined the AC. He was appointed by David Brown, Governor in Ŧaraṅgampãdi, as an AC-representative and agent in Porto Novo. When Porto Novo was attacked by Mysore troops in 1780, Gowan was captured as a hostage. At that time, Gowan transcribed his experiences (available in det Ostindiske Governement: Kolonien Trankebar, Rigsarkivet, Copenhagen), which PSR qualifies as ‘meticulous’p. 281. In p. 281‒350, PSR provides us with a slightly edited, easily readable full text of Harrop’s notes — another invaluable passage.

The Journey’s end (p. 355‒360) is an engaging end chapter. Although short, this epilogue includes many striking remarks by PSR. This chapter includes perplexing socio-cultural questions that prevail today, consequent to the impact of the Danes and other Europeans in Ŧaraṅgampãdi. As I read this chapter, new chimes of subaltern-logic bell rang in me. PSR refers to remarks of a less-known traveller Hans Christensen Mesler in the Ŧaraṅgampãdi‒Nãgapattinam region, recorded in the Journal paa Reisen fra Kiøbenhavs til Trankebar 1708‒1711. The reference to Mesler’s remarks will certainly stimulate future investigators, concurrently enabling them to see the sociological past of colonial Ŧaraṅgampãdi through a fresh pair of lenses.

One major strength of this book is the availability of plain-English texts of vital records made by various people associated with the Danish administration in Ŧaraṅgampãdi in the 17th‒19th centuries. Thanks to PSR for providing us details from official documents and personal diaries, by translating them from Danish into English, and even ‘translating’ some from ‘olde’ English into modern English! A glossary of Indian terms (p. 361‒362), a bibliography of primary sources (p. 363‒372), a list of archived materials from Rigsarkivet, Copenhagen (p. 373‒374), notes (p. 375‒408), and an index of keywords (p. 409‒424) are indeed user-friendly. I will readily compliment PSR for thoughtfully including a ‘notes’ section that comprehensively explains every secondary, yet important, information. The section Tranquebar — a time capsule (p. 13‒17) compactly captures milestone events in Ŧaraṅgampãdi’s history between 1618 and 1845; a diligent inclusion.

It will be impossible for me to analyze and discuss all details beautifully presented by PSR in this book. I have touched on some, as samples, especially those that appealed to me and those I thought would interest readers of this journal. On the whole, I experienced fulfilment. This book unveiled many dimensions that were new to me pertaining to a tiny segment of Tamil-speaking India. I am confident that reading Unheard Voices will be a rich experience, as much as I experienced. The University Press of Southern Denmark deserves thanks for a splendidly neat production. This book, I am sure, will be a prized inclusion in both personal and public libraries of India, because it shines a bright beam of light on a European culture that subtly varied from that of the Portuguese in Mylãpôre (Chennai), French in Põndiçéry and Karaikkãl, Dutch in Pazhavérkãdû and Çadûranga-p-pattinam (both near Chennai), and the English in Fort St. George (Chennai) between the 17th and 20th centuries!

- Ravenstein, E. G. (Translator), A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499, Burt Franklin, New York, 1898, p. 238.

- Trap, J. P., Billeder af Bberømte Danske Mænd og Kvinder, der have Levet i Tidsrummet fra Reformationens Indførelse Indtil kong Frederik VIIs Død, Steen & Son, Copenhagen, 1867‒1869, p. 466.

- Fihl, E., Venkatachalapathy, A. R. (eds) Indo–Danish cultural encounters in Tranquebar: past and present, Dev. Change, 2009, XIV, p. 319.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A., The Çolas, Madras University Historical Series # 9, University of Madras, Madras, 1935, p. 812.

- Ramachandran, C. E., Aha-nãnûrû in its Historical Setting, University of Madras, Madras, 1974, p. 148.

- Pillai, R. S., Çilappaŧikãram, Tamil University, Ŧanjãvûr, 1989, p. 150.

- Schoff, W. H. (Translator and Annotator), The Periplus of the Erythræan Sea (translated from Greek), Longman, Green, & Company, London, 1912, p. 323.

- Engelhardt, H. M., Tanker om oplysnings udbredelse blant Indianerne. Anledning af det Tranquebarske selskabs opgave: hvilket er det beste middel til at bringe oplysning blant malabarerne, The Royal Library, Copenhagen, 1790, # 425, p. 40.

- Wirta, K. H., Dark Horses of Business: Overseas Entrepreneurship in Seventeenth-century Nordic Trade in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, University-of-Leiden Repository, https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2975215/view, accessed on 19 December 2021.

- Ferguson, D., Roy. Asiat. Soc. Great Brit. Ire., July 1898, 625‒629 (no volume number available).

- Phillpotts, B., The Life of the Icelander Jón Ólafsson: Traveller to India, Hakluyt Society, London, 1923, p. 238+p. 290.

- Rao N K, Vagiswari A, and Louis C, Father J. Richaud and early telescope observations in India, Astr. Soc. India, 1984, 12, 81‒85.

- Herdendorf, C. Captain James Cook and the transits of Mercury and Venus, Jour. Pac. Hist., 1986, 21, 39–55.

- Ramanujam, P. S., An overlooked 18th-century Danish astronomer, Today, 2018, https://physicstoday. scitation.org/do/10.1063/ pt.6.4.20180921a/full/, accessed on 22 December 2021.

- Anonymous, Mag. Hist. Chron., 1762, 32, 177.

- Jensen, N. T. The Tranquebarian Society — Science, Enlightenment and Useful Knowledge in the Danish-Norwegian East Indies, c. 1768‒1813, p. 45, no date available, https://pure.kb.dk/ws/files/21499948/The_Tranquebarian_Society.revised_version.11022015.pdf, accessed 26 December 2021.

- Robinson, T. F., William Roxburgh ‒ the Founding Father of Indian Botany, Phillimore, West Sussex, 2008, p. 304.

- Mohanavelu, C. S., Annotated Bibliography for Tamil Studies Conducted by Germans in Tamil Nadu during 18th and 19th Centuries: A Virtual Digital Archives Project, The University Grants Commission, New Delhi, 2010, p. 539, https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/ druid:xh950zd4962/ UGCPROJT2111.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2022)

- Raman, A., Sci., 2017, 113, 368‒369.

- Rastogi, N., Jour. Lepr., 1984, 52, 541—543.

- Larwood, H. J. C., Roy. Asiatic Soc. (N.S.), 1962, 94, 62‒76.

- Allen, R. B., Tempo, 2017, 23, 295‒313.

- Bouchardat, A., de la Glycosurie, ou, Diabète Sucré: son Traitement Hygiénique: avec Notes et Documents sur la Nature et le Traitement de la Goutte, la Gravelle Urique, sur l’Oligurie, le Diabète Insipide avec Excès d’Urée, l’Hippurie, la Pimélorrhée, &c., Librairie G. Baillière, Paris, 1875, p. 336.

Originally posted at https://www.madrasmusings.com/vol-32-no-1/unheard-voices-of-tranquebar/

and https://www.madrasmusings.com/vol-32-no-3/unheard-voices-of-tranquebar-ii/

Reprinted here by kind permission of the reviewer.

ANANTANARAYAN RAMAN

CSIRO, Floreat Park,WA 6014, Australia

Email: anant@raman.id.au