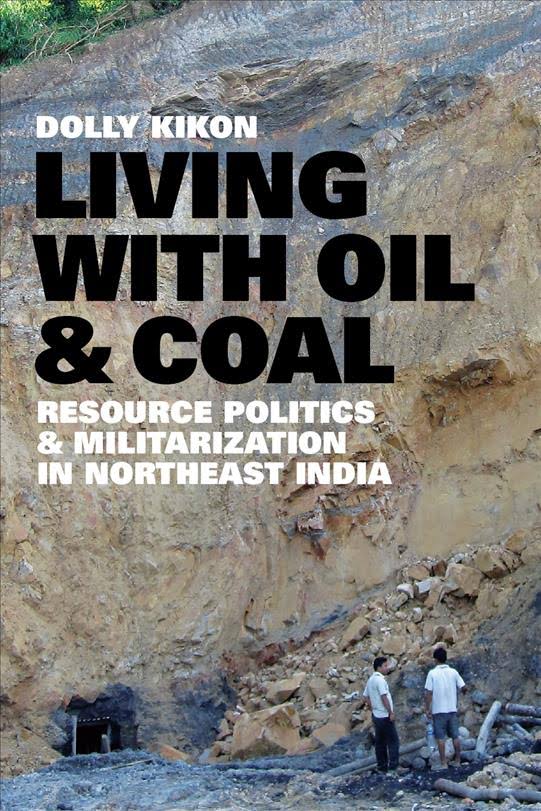

Foothills. Such a lovely word. It signals an elusive geography—neither high-altitude mountains, nor flatlands or plains. As we learned from postcolonial theorists like Homi K Bhabha and Edward Said, foothills have that quality of the creative in-between space where differences can flourish. In anthropologist Dolly Kikon’s masterly crafted book Living with Oil & Coal: Resource Politics & Militarization in Northeast India (2020) we are taken to the foothills of Assam and Nagaland.

North East India and the borders separating the states in the region are all post-independence creations. Yet, an older colonial logic is at work, based on the idea that hills and valleys should be separated and governed differently. The British had their reasons for this, not least to facilitate the establishment of the tea industry in the second-half of the 19th century. The tea planters were endowed generous land grants in the Brahmaputra Valley, but had to stay out of the hills to prevent upheavals in these “sensitive” frontier tracts.

The British eventually settled for indirect rule in the hills, governing through intermediary chiefs and village councils, based on the customary laws of the respective community. The legal and administrative exceptions given to the hill areas have survived through the postcolonial period in the form of district councils established under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution and, in the case of Nagaland, through the special provisions under Article 371(A) of the Constitution of India. The most critical aspects of these exceptions relate to community rights to land and natural resources.

If the state holds the right over natural resources in Assam, such rights are vested with the indigenous or tribal communities in Nagaland. This difference is central to the stories Kikon tells about life and livelihoods in the foothills.

Buy Living with Coal & Oil on Bookshop.org