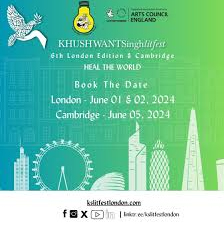

Khushwant Singh is a household name for those in the Indo-Pak literary sphere. The Khushwant Singh Literary Festival ran for its 6th session in June 2024 with the theme ‘Heal The World’.

Khushwant Singh is a household name for those in the Indo-Pak literary sphere. The Khushwant Singh Literary Festival ran for its 6th session in June 2024 with the theme ‘Heal The World’.

Mr Fakir Aijazuddin OBE, a renowned Pakistani art historian and curator of Sikh Art, paid tribute to his friend Khushwant Singh, describing their last meeting in 2014 when they both knew it was goodbye. As he spoke fondly of his friend, and of the close ties between the Muslim and Sikh communities in Punjab, there was silence in the Brunei Gallery theatre as everyone hung on to his words.

His charisma and way with words made it easy for the audience to time travel to Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s reign, when his ancestors, The Three Fakir Brothers, held trusted positions in court and were able to negotiate and secure assets and deals for the kingdom on behalf of the Maharaja. Indeed, it was Mr. Aijazuddin himself who had carried Khushwant Singh’s ashes to their final resting place in Hadali, present day Pakistan, fulfilling his promise to his friend to lay him to rest in his place of birth.

During his lifetime, Khushwant Singh worked tirelessly to promote peaceful relations between India and Pakistan. He also advocated for women’s rights worldwide. The Festival meets every year to celebrate a life spent in selfless Seva of a world increasingly in need of compassion and tolerance.

It was refreshing to see the shared values demonstrated by the panellists. Dr S Y Quraishi’s electrifying love for his country and impeccable work ethic as India’s first Muslim Chief Election Commissioner, Harinder Singh’s beautiful rendition of the concept of ‘Ik’ in Sikhism, Imtiaz Dharker’s poetry reading from her latest collection, ‘Shadow Reader,’ which tickled and silenced the audience all at once, can be found here, as well as the rest of the session videos from the Festival. I did not want to write a boring report on each and every talk held at the Festival because I knew I could not do the speakers justice. Instead, I choose to focus on the theme of Healing; that of Oneself and the World we live in.

Our world as we know it today, is riddled with disease and greed. The speakers, all sharing a deep love and reverence for their Indian heritage invite the audience to dwell on what it would take to make ourselves and our world well again. When I say Indian heritage, I include Pakistan and Bangladesh, because as much as we’d like to deny it at times, we were all Indian once.

Advait Kottary, an engineer, wrote the novel ‘Siddhartha’ during an introspective period in his life. He had achieved everything our material world would consider successful but was still unfulfilled, and he set out to explore Siddhartha’s journey. The irony is not lost on Advait. He has also produced the famous Bollywood musical, ‘Jaan-e-Jigar,’ and acted in international productions such as Beecham House.

Paul Waters and Subhadra Das, author of ‘Uncivilised: Ten Lies That Made The West’, discussed, among other things, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and its origins. Maslow was challenged by anthropologist Ruth Benedict to study the Blackfoot Nation. What Maslow discovered was, that the Blackfoot nation were very much a society based on the principles of ‘nobody left behind.’ ‘It’s not a question of whether you are civilised. The fact that you exist as a human is all that is required.’ stated Subhadra. An individual should aspire to be self-actualised (the top tier of Maslow’s Needs) but only if it meant serving their community. True self-actualisation is selfless. An individual achieves true power through transcendence. We need to be willing and able to contribute selflessly to our community.

Lynne Jones’ comments on the climate crisis and ‘capitalism gone wild’ reveals where we have gone wrong in interpreting the Hierarchy of Needs. It is possible to live in a capitalist economy, as long as the primary needs of water and shelter are regulated by the government. It is the job of the government in a capitalist structure to ensure that corporations do not make large profits off of people’s suffering. Our society is diseased because we are being forced to line the pockets of CEOs every time we fall ill or ask for basic necessities.

This brings me to the question of how we heal ourselves in a society adamant on keeping us sick and stressed. Mr. Aijazuddin stated that the spoken word, art, history and literature are all different ways of worship. Every time we admire a piece of art or read a novel by our favourite authors, we are healing a piece of ourselves. In her book, ‘The Lost Homestead’, Marina Wheeler talks about the paradise her mother Dip Singh had to bid adieu to during Partition, the small town of Sargodha in present-day Pakistan. Dip Singh’s story is a beacon of hope amongst the generational traumas many continue to experience as an aftermath of Partition. Her bravery and ability to overcome the hurdles of Partition and embrace a new life in England with her husband, broadcaster Charles Wheeler present a strong example to our diaspora. Marina Wheeler reflected on how, towards the end of her mother’s life, she realised that she wrote ‘The Lost Homestead’ for herself, rather than for her mother. Dip Singh had already reached the level of self-actualisation allowing her to be content with her life’s journey.

Nadia Kabir Barb, Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi and Tahmima Anam had a lively discussion about self-censoring art in order to please family (the familiar ‘Log Kya Kahengey trope) and staying true to yourself through your life’s work. Tahmima’s trilogy centres around the Bangladeshi Liberation movement and her latest novel, ‘The Startup Wife’ is a book she feels is closer to her lived experience. As writers from the diaspora, we often feel obliged to explore themes and tropes around Partition and the Independence movements of 1947 and 1971.

I feel it important to also highlight Ayesha’s comments on the atrocities committed against Bangladesh in its liberation movement and the Pakistani state’s lack of acknowledgement of these deeds. We cannot heal until we first acknowledge the harm done to ourselves, and the harm we have done to others.

The festival dealt with some serious and tragic, although necessary, themes however we were glad to be entertained by occasional pinches of Masala Mirch from our speakers. Ayesha spoke about how her cycling instructor had casually commented to her that most of his clients were South Asian and Arab women who hadn’t had a chance to ride a bike earlier in life. Ayesha initially wanted to use this as material for her novel. Eventually she decided against it, fearing that she would be reinforcing a stereotype about women from the Middle East and South Asia. An audience member very kindly told her that it would have been okay for her to write about it, because it was a fact, to which Tahmima Anam quipped, ‘He is giving you permission.’ As South Asian women, we are used to needing permission, so imagine our delight at it being granted to one of ours so easily!

On the topic of (literal and figurative) Masala Mirch, Pinky Lilani, author of Spice Magic and Coriander Makes a Difference, joked that she would try not to speak for more than 20 minutes, because according to research she has conducted, after the 19-minute mark:

‘20% of the audience starts thinking of what they’re going to do as soon as the talk is over, 20% are reminiscing, 12% are thinking of religion and 17% are having erotic thoughts.’

She forgot to mention the remaining 31% who are no doubt thinking about her famous Masala Wala Aloo. Reader, I am proud to belong to this majority.

The Khushwant Singh Festival is made possible each year due to the generosity of its patrons and volunteers. Please do consider donating here.