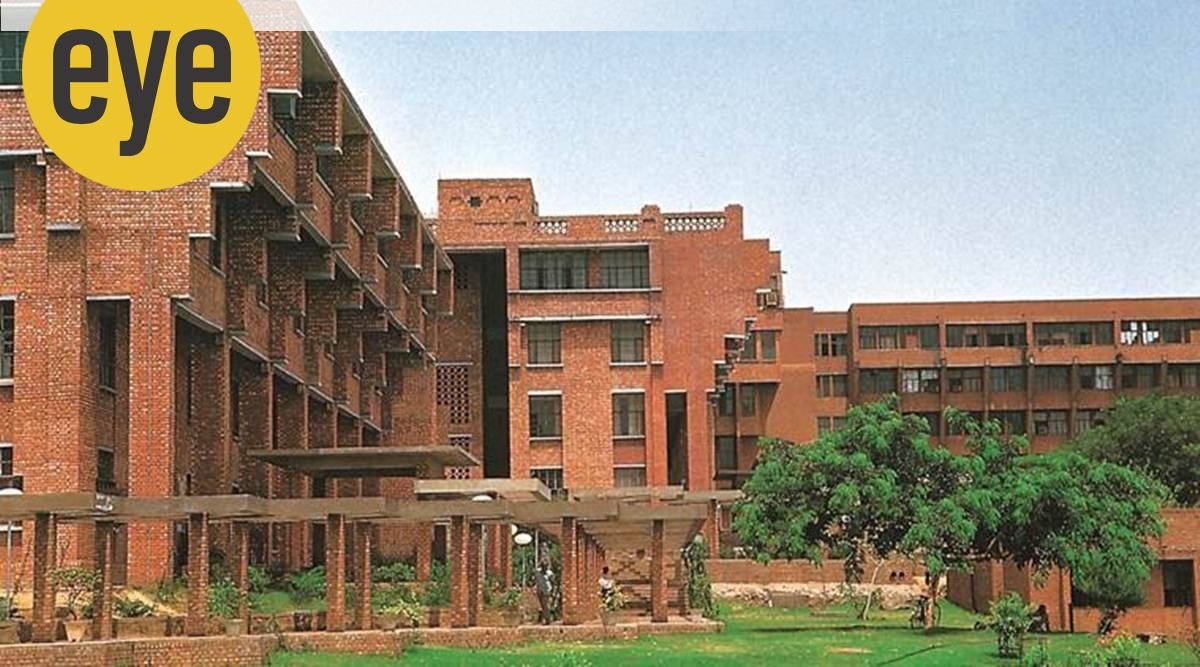

Jawaharlal Nehru University is an idea which is dreamy and irreverent, challenges the stereotypes, breaks traditional moorings, is Leninist in its thought process but Gandhian in ethos and that makes it mystical and intriguing, and, in certain ways, spiritual. For an outsider, JNU is intimidating but for someone who has lived on the campus as a student, not as a teacher, JNU is endearing. I know this because I spent eight glorious years on campus as a student and I was not a communist. And, of course, neither was I an anti-national.

I joined JNU in 1986, when communism was fading the world over and I exited JNU when the Soviet Union was no more. So, while reading this book written by professor of English, Makarand R Paranjape, I was not surprised that he failed to understand JNU. He seems intimidated by the idea called JNU despite being a professor for more than two decades in the campus.

I dare not say that he wrote this book out of hate, rather, while writing, he believed that like the Communist Manifesto, his book would trigger a “revolution” and JNU would be wiped clean of the “malaise” that makes it the best university in the country. Before I joined JNU, I studied at Allahabad University, which then was called the Cambridge of the East, but it was JNU which transformed non-entities, many like me, from small town, lower middle-class boys into men ready to fight for universal values.

Of course, JNU even then was a citadel for communist ideas but it was an intellectualism of a very high order, refreshed by democratic values and egalitarianism, which abhorred any kind of sectarianism, communalism and casteism, and was not intimidated by the all-powerful establishment. That is why it invited the wrath of Mrs Indira Gandhi. So, if the Narendra Modi administration is angry with JNU, I am not surprised. I would have been surprised if it had surrendered to the hegemonic right-wing ideology.

I can understand professor Paranjape’s anguish when he writes “Everything is political. Or politicised. Anti-government activists thriving at the government’s expense. This was what JNU socialism seemed to boil down to.” I was aghast to read that a professor of his calibre equates “anti-government-ism” with “anti-National-ism”. He writes, “…I challenged the overwhelmingly anti-government, one might also say anti-national, stance of the JNU student union.”

When a professor borrows a phrase like “tukde tukde”, I am sure he has his reason but I was rather surprised when he relates Gandhi with violence. While lecturing students after the Kanhaiya Kumar episode, he says, “Gandhi was forced to settle for the violence of the state in maintaining law and order. That to him, was preferable to indiscriminate mass violence.” Non-violence was the basic essence of Gandhi, the reason for his existence, and to even tangentially read otherwise will be a wrong reading of Gandhi. It was this reason that he was iconised by Albert Einstein, Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King.

If there is one university which imbibed the basic essence of Gandhi, it is JNU where disputes were/are not sorted out by the use of violence but by constitutionally mandated means. I am not denying that there were, and are, no exceptions but to deride students for peaceful protests and paint a different picture smacks of an ideological bias and personal prejudice. I am glad he did not hide his liking for PM Modi. He writes, “At his best, Modi can be inspiring and visionary … A master political strategist, he is also determined, driven, even, a visionary leader…” To praise Modi, he coins a new phrase for nationalism. He writes, “NaMo nationalism, this is the chant of the mantra of unity, not division.”

I will definitely not call this book a rant of a professor seeking endorsement from the left liberal and, in its absence, finds them “degenerate” and his friends wonder, “how the dominant, left liberal, Congress-sponsored narrative about India is so durable.” I can understand his pain when he writes, “I realised that even after teaching diligently, faithfully, and one might even say inspiringly for over twenty years, I found no recognition, let alone affirmation in JNU … here being the most published professor did not count for anything at all.” He very honestly poured his heart out. His angst is justified but then that is what JNU is. Even recognition to academic stalwarts like Romila Thapar, Bipan Chandra, Namvar Singh, Kedarnath Singh did not come easy. That is JNU.

There is no doubt that at times his language is lucid, turn of phrases are beautiful, throws some thought-provoking ideas too but he limits his scholarship to only one kind of narrative that makes the book attractive to his right-wing friends and ugly to left-liberals. That is ironical. But such is the time when objectivity is insane and subjectivity is a virtue.

Source: The Indian Express