While most people are right now thinking of Pratap Bhanu Mehta, I am thinking of two of my fellow Stephanians: Sanjeev Bikhchandani and Harsh Mander.

Let me briefly explain why.

I know how much of himself, together with his associates, Sanjeev invested into founding the Ashoka University. Whenever he referred to the institution in the course of our conversations – though such references were few and far between – I could catch the thrill of pride in him, which he tried to hide, lest it amounted to disloyalty to his alma mater, St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. He dreamt of an exemplary institution in ‘liberal’ higher education. Very likely, this was the residual Stephanian element in him.

I wonder how feels about Ashoka University now. I have been worried about it for a few years. Thank God, it still took a few years for matters to come to a head. I expected this to happen sooner.

Unlike some other Stephanians, Sanjeev understood the content of liberalism positively and constructively. While some other Stephanians equated liberalism with ‘being irreverent’, Sanjeev understood it as a climate of intellectual freedom that transcended the cultural proclivities of the times. So, while the rest of the society went the science-technology/skill-formation way, Sanjeev wanted to make education a celebration of the best that is thought and known in the world, as Matthew Arnold put it.

Tragic heroes are said to be out of sync with their times. Sanjeev hatched the liberal dream when the age of liberality had gone past in India, at least for the time being. To me this was clear enough a decade and a half ago, given my experiences as the Principal of the said St. Stephen’s College. Though the quintessence of liberalism is freedom to express oneself authentically through one’s work, I was pummelled for doing so. I am not complaining but facts must be faced. Tyranny is not only what is done by those we dislike. Tyranny is also what we practise towards those whom we dislike; and it is tyranny, even if it is perpetrated in the name of liberalism.

There is a terrible misunderstanding in our idea of liberalism. It is associated with what the elite do. So, liberal heroism has its preferred haunts; JNU, for example. To us liberalism has never been a way of life. It was, and is, a posturing, a sort of grand-standing. (There are exceptions to this; and to that, anon.) So, one is liberal in set and stereotypical ways, in designated spaces. Can one take one’s liberal baggage to the villages, for example? To the informal sector? To the spiritual anguish of a people? To the existential trauma of the millions?

Specific to Sanjeev, I ask:

- Can one be liberal in the world of commerce and industry?

- Can one be liberal in politics?

Ironically, it is the illiberalism of the industrial-commercial world that enables us to afford the liberalism of culture and (its subset) education. This is not a negative reflection on Sanjeev, whom I hold in boundless affection.

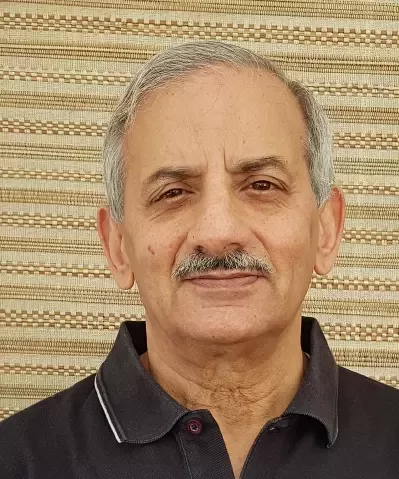

I have to acknowledge how deeply I cherish my association with him. If I recall, say, five faces as particularly dear to me from among the alumni, he will be on the list. His generosity to St. Stephen’s is something I have not duly acknowledged. His level-headedness, which prosperity could not upset, never failed to appeal to me. The quiet and controlled dignity, the understated steadfastness of purpose with which he went about all that he took upon himself, are winsome personal hallmarks. I am not in touch with him, knowing the place of a retired man, who, according to the Indian world view, must be in van-vas, which I am. So, I am now free to tell the truth, with far less risk of being misunderstood.

The honest truth is this. No one likes anyone to be different from himself. It is dishonest to damn Modi for it. He is not alone in this business. We are unlike Modi only in degree, not in kind. During my tenure as Principal, I had to endure hundreds of bonsai Modis. I’d rather deal with the genuine Modi than his pocket editions. One such pocket edition was Sunil Kumar Singh, the abominable Bishop of the Church of North India in Delhi. The rest I don’t need to mention.

What has happened to Prof. Mehta, and to my friend Sanjeev, betokens the failure of Indian higher education in India. The space for liberalism shrank in India, ironically, through higher education. But for the so-called educated, most Indians would have lived in greater freedom and dignity. And it is time we realized that corporate businesses hold out a real threat to liberal education, as will become increasingly clear in the days ahead.

Now that Prof. Mehta has resigned, I hope he will think of living the liberalism that he professes. That is where I want to recall, with respect and admiration, my friend, Harsh Mander.

Unlike Mehta, Mander does not confine liberalism to elite niches. He takes it to the business and bosom of the people. This is the place for me to acknowledge my profound gratitude to Harsh. I contacted him when I felt that additional inputs needed to be made to reinforce the humanistic and liberal timbre of the education that St. Stephen’s practised. He responded promptly, and designed a course titled ‘Engaging with Unequal India’. What’s more, he administered the course himself for long years. And, do note this, he did so without expecting or receiving any financial recompense or indeed any recognition beyond the affectionate thanks of the College and of his students. This continued till I retired in 2016.

Harsh Mander’s liberalism will not be choked to death by adversity; for he lives it. Of course, he does and will face difficulties. He too may have to scream the by-now-familiar words, ‘I can’t breathe’. But he will breathe, nonetheless. Prof. Mehta could wither away. This is no reflection on him. It is a concern born out of the growing insubstantiality that supervenes academia, where, as Shakespeare says, it is ‘words, words, words; nothing but words’ all the time.

The time has come to shift from the liberalism of words to the humanism of deeds. This calls for a shift from head to heart – a call which needs to be stated even if it sounds tepid to those who are intoxicated with the heady wine of their own rhetoric.